Essay

May 14—We have reached our cruising altitude. Use of electronic devices is permitted at this time.

I turn 25 tomorrow. Importantly, this means I can now legally rent a car at the next offsite. People have asked how I feel about reaching a quarter century. My party line has been that I postponed the marking of the occasion due to an especially busy stretch of work. I write this on a plane to Seattle. I’ll be spending my birthday in a seven-hour in-person meeting (I do not lament this; there is no better birthday for me than first-hand watching Alex talk about passkeys). But while I perhaps have delayed a birthday dinner, I think everyone knows I’ve been lying to say I have no thoughts. This year I had one question on my mind: do we change as people as we get older?

While this question has been on my mind for a bit of time, I credit this wonderful article in The New Yorker for providing my mind with the intellectual playground it sought to explore this concept. In weaving between stages of life, the piece ultimately explores how we are expected to toggle between the dominating presence that is our present moment and the shadow cast by a past we may not remember. Author Joshua Rothman admits that all he remembers from age four was a “glimpse of my father’s face perhaps smuggled into memory from a photograph.” While memories of our early years may actually be mirages transplanted from later years, that younger self who we may actually not even remember all that well is fairly deterministic of the person we are today.

I first read this article about a month ago, the last time I flew West. To be honest, I remembered the scientific part a little differently. Rothman describes what was known as the Dunedin study, which tracked 1037 people in New Zealand from age 3 through age 45. At age 3, each child was rated on 22 aspects and accordingly placed into one of five groups. 40% were placed into a group labeled “well-adjusted.” 25% were placed in the “confident bucket.” The other categories were reserved, inhibited, and “undercontrolled” (15%, 10%, and 10% respectively).

Rothman claims that by age 18, “certain patterns were visible.” The cited evidence is that those in the inhibited and undercontrolled buckets “had stayed truer to themselves,” with the inhibited kids at age 18 “significantly less forceful and decisive.” The authors concede that while the original children from the confident, reserved, and well-adjusted buckets (80% total) stayed broadly in those genres, the distinctions between them became less defined. So new lines were drawn, and the original five tags were condensed to three. A large group who did not seem to be on a set path, and then two smaller groups: one “moving away from the world,” and one “moving against the world.” Researchers found that in life, those in that latter group had a more indelible disposition and were more likely to get fired from jobs or fall into gambling addictions. The scientists concluded that through “such self-development…we curate lives that make us ever more like ourselves.”

A month ago, I was hell-bent on fatalism. As I found myself writing similar journal entries as years ago, this study gave me solace. Maybe I couldn’t change, but maybe, too, that was expected. We choose the paths we were always going to; deviations are simply the aberration of different elements that lead to the same response in new contexts. I read the Dunedin study again and laugh. Sure, we largely continue down an expected path. But if the authors ended up with three buckets for over 1,000 people, it seems the range of outcomes perhaps has more variance than I had remembered.

Rothman next compares two Tims in his life. One, his father-in-law, is adamant his life is one that has seen little change. Tim number two, a friend from high school, believes Merriam Webster would define his life by change. Yet, Rothman believes that in the time he has known his father-in-law, he has changed quite a bit. He also pushes back on his high school friend’s definition of change as his constant personality trait, writing, “for as long as I’ve know him [Tim 2], he’s been committed to the idea of becoming different. For him, true transformation would require settling down; endless change is a kind of consistency.”

While it may not be possible to declare the answer one way or another, we can perhaps explore what it would mean in a world where one was explicitly true. If we change, I’d like to think it is in line with the following description:

To be changeable is to be unpredictable and free; it’s to be not just the protagonist of your life story but the author of its plot. In some cases, it means embracing a drama of vulnerability, decision, and transformation; it may also involve a refusal to accept the finitude that’s the flip side of individuality.

I have tried to grasp a meaning for the words that come after the final semi-colon for a month and am at most 10% of the way there. If you have any ideas, I’d love to hear them. But what precedes that mighty semicolon resonates. It is the rallying cry of free will. It is a cacophony of noise drowning out any self-pity we may feel at any given moment. Vulnerability often means acceptance of a past, one that can not be changed.

James Fenton’s poem “The Ideal” stares at me on my console:

A self is a self.

It is not a screen.

A person should respect

What he has been.

This is my past

Which I shall not discard.

This is the ideal.

This is hard.

In reflecting on the poem, Rothman offers the following breakdown for Team “We stay the Same”:

In this view, life is full and variable, and we all go through adventures that may change who we are. But what matters most is that we lived it. The same me, however altered, absorbed it all and did it all. This outlook also involves a declaration of independence—independence not from one’s past self and circumstances but from the power of circumstances and the choices we make to give meaning to our lives.

I once again do not find this idea contradictory to the earlier explanation as to why we do change. This does not dismiss our ability to change; rather it says that the question is moot because life should instead be viewed through the lens of the memories we encountered and created. It doesn’t matter if our actions were a result of us staying the same and new situations begetting different responses or if our own permeability has caused new outcomes. What’s important is our life of experiences.

This reflection is a fun exercise because I keep changing what side I am on, even in the midst of writing it. Last night I sat next to my roommate Alex at a party. We’ve been close friends since tenth grade—close to ten years. I ask him this question, and he responds that he thinks we do change. I push back—describing through technicalities why I’ve become convinced we do not change. We smile, contemplating each other’s side. 24 hours later, have I come back to his team so quickly? Or perhaps, as I wrote last month, the answer is not binary. Maybe they do overlap. As Rothman articulates, “by committing himself to a life of change, my friend Tim might have sped it along. By concentrating on his persistence of character, my father-in-law may have nurtured and refined his best self.” The two Tim’s perhaps best demonstrate this paradox that the answer is not prescriptive. Alex reminded me that I once again was living in a self-induced binary world.

As our journey nears its end, Rothman concedes a valuable point. While we may not know which answer is true, the “passage of time almost demands that we tell some sort of story.” We undoubtedly are different people than we were 10 years ago. Back then Alex and I shared a hotel room for a business competition called DECA; today we share an apartment in the West Village. Our lives are different. But these life philosophies are how we connect the dots.

A story that neatly divides your past into chapters may also be artificial. And yet there’s value in imposing order on chaos. It’s not just a matter of self-soothing: the future looms, and we must decide how to act based on the past. You can’t continue a story without first writing one.

Sometimes these past chapters we write too unambiguously. If we didn’t change, are we imperturbable? If we were molded by events, have we become better versions of ourselves? Rothman ends his sojourn in looking for an answer with a beautiful conclusion, stating that “we change, and change our view of that change, for as long as we live.”

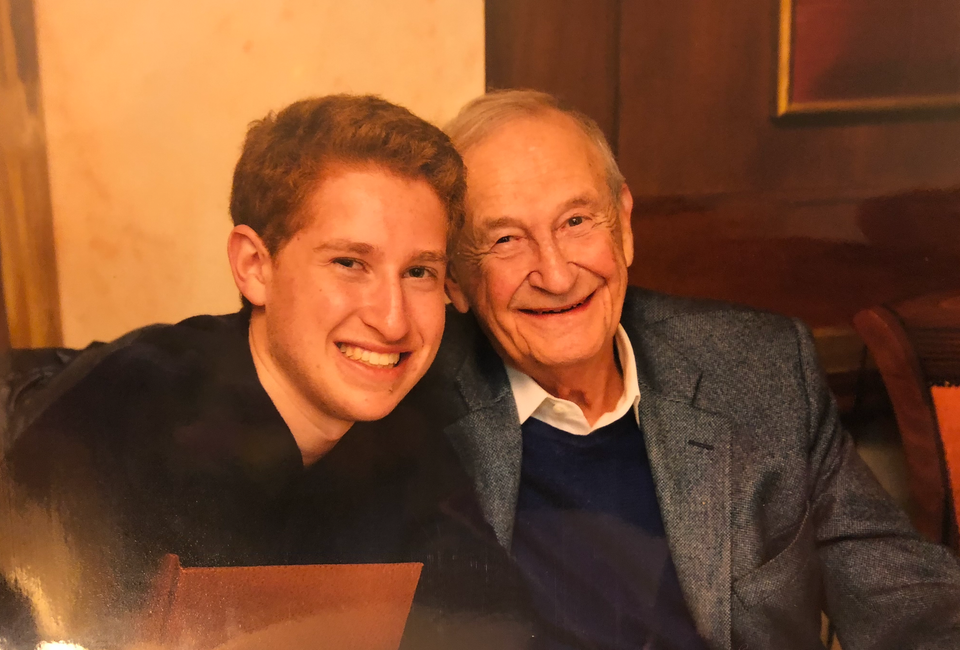

I asked my Grandpa Ken if people change. The exceedingly rational person he is, my Grandpa eschewed the core question—asking me why I tortured myself pondering the depths of such unknowns—and instead reframed the question in his answer. “I have learned that we can’t change other people.” If we can’t change others, is it naïve to think we can change ourselves?

April 16, 2023. Transcription from a voice memo

Indelible. You can not change your past. You may remember it differently. May have peak-end theory which is great. May look back nostalgically on stuff that wasn’t good. I do. Maybe not because you’re looking back nostalgically but because you longer have to live it.

But that is all still you. If you think about Daoism or Nietzsche about shame—that is you. You should improve. You will improve. This is not me saying everything is ok. This is not saying that if you view something from an unhealthy lens that it is ok to keep it. What I am saying is that you can’t run from it. You are you. You will never win with a mask. Never.

You can come up with stories. But you are you. Maybe you don’t feel confident because you’re not looking for anyone to tell you you’re great. It is your job to love yourself and all of your imperfections. You should probably look for people who feel similarly but it is not their job to tell you that. You can never love yourself until you can talk about yourself. It is impossible. You can only love yourself if you can talk about yourself. Maybe you are not proud. Maybe parts of you made you messed up. But it’s you. You may pick up a hobby when you are 26. But narratives from the first 25 years are there. Maybe you will change them. But it starts with indelibility.

May 14th—The Plane is preparing for landing, please lock your tray tables and stow your belongings

With my laptop away, I go through old photos. Eating meals in foreign places. Dancing at festivals. Playing with my dog. Remembering moments from the early Footprint days with screenshots of emails. I smile. I don’t know if I’ve changed. Maybe I was always going to be writing this update on this plane. Perhaps I have changed. But it doesn’t matter. I know I wouldn’t trade this path for the world.

I don’t know if we change. When I re-read my journal entries from a year ago, it certainly seems that we do not. When I re-listen to my 3 AM voice memo above, it seems to concur with James Fenton’s poem; we must love—or accept and forgive— the past events that can not be changed. In many moments, I think we can have our memory of those events changed as the purpose of them plays out in a later present. I had wanted this update to be fatalistic. Write that we don’t change. But I am a romantic, so I am not surprised to have this about-face: praising free will and our ability to alter our own path. Despite a lot of evidence pointing me to the contrary, perhaps it is best accepted but not inherently believed. Though if that is my perspective, did I really change, or just return to my natural state?

Sunset Jesus by Avicii plays. “California, don’t let me down…my dreams are made of gold. My heart’s been broken and I’m down along the road. But I know, my dreams keep fading 'til I get old. Breathe for a minute, breathe for a minute. I’ll be ok.” The melody crescendos. The wheels touch down. It’s midnight ET. The 14th has become the 15th. I look forward to another year of definite memories. Of possible change.

Goals From Last Month

Publicly launch KYB

- Done—blog post here

Publicly launch our Card Vaulting & Components APIs

- Done

Alpha version of our App Clip experience

- Done

Hires from last Month

We are very excited to be bringing on Bruno Batista as a senior product engineer. Bruno has 14 years of experience working on frontend development. In 2017, Bruno moved from Brazil to Munich to become the first frontend engineer (and employee 11) at Personio, where he helped build the first product and team (where he met Rafa :)). Brimming with an entrepreneurial spirit, Bruno was also the founding engineer at Ezlike, a platform for optimizing ads on Facebook, that was acquired by Gravity4 in April 2015. He also helped build Tamboreen, Ezlike's B2C ad optimization product, which was acquired by Magazine Luiza in December 2014. We could not be more excited to welcome Bruno to the team!

Goals For This month

- Launch App Clip to prod (early access in June)

- Launch advanced decisioning workflows (first-party integrations with Alpaca and Apex)

- Meaningful work on analytics dashboard

- Meaningful work on international capabilities

Open Roles for Recruiting

Backend Engineer

- Ideal profile: Skilled in building performant, scalable distributed systems. Experience in Rust + payments tech is a huge plus.

Company We Are Looking for Intros To